Pang Yande Chinese Folk Art Painting on Leaves Buy Online

| Chinese painting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A hanging scroll Chinese painting past Ma Lin in 13th Century. Ink and color on silk, 226.6x110.iii cm. | |||||||

| Danqing painting, a department of Wang Ximeng's A Thou Li of Rivers and Mountains ( 千里江山圖 ). | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國畫 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中国画 | ||||||

| |||||||

Chinese painting (simplified Chinese: 中国画; traditional Chinese: 中國畫; pinyin: Zhōngguó huà ) is one of the oldest continuous creative traditions in the world. Painting in the traditional style is known today in Chinese as guó huà (simplified Chinese: 国画; traditional Chinese: 國畫), meaning "national painting" or "native painting", as opposed to Western styles of fine art which became popular in China in the 20th century. It is besides called danqing (Chinese: 丹青; pinyin: dān qīng ). Traditional painting involves essentially the aforementioned techniques every bit calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in blackness ink or coloured pigments; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the well-nigh popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished piece of work tin exist mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Traditional painting can also be done on album sheets, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other media.

The two principal techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Gongbi (工筆), meaning "meticulous", uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimit details very precisely. Information technology is often highly colored and normally depicts figural or narrative subjects. It is often good by artists working for the royal courtroom or in independent workshops.

- Ink and wash painting, in Chinese shuǐ-mò (水墨, "water and ink") also loosely termed watercolor or castor painting, and also known as "literati painting", as information technology was i of the "iv arts" of the Chinese Scholar-official class.[1] In theory this was an fine art proficient by gentlemen, a distinction that begins to be fabricated in writings on fine art from the Vocal dynasty, though in fact the careers of leading exponents could benefit considerably.[2] This style is also referred to equally "xieyi" (寫意) or freehand way.

Landscape painting was regarded as the highest grade of Chinese painting, and generally nevertheless is.[3] The time from the Five Dynasties menstruum to the Northern Song period (907–1127) is known every bit the "Great historic period of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such equally Jing Hao, Li Cheng, Fan Kuan, and Guo 11 painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to propose rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

Specifics and study [edit]

Chinese painting and calligraphy distinguish themselves from other cultures' arts by accent on motility and alter with dynamic life.[4] The practice is traditionally start learned past rote, in which the principal shows the "right way" to draw items. The apprentice must copy these items strictly and continuously until the movements become instinctive. In contemporary times, argue emerged on the limits of this copyist tradition within modern art scenes where innovation is the rule. Irresolute lifestyles, tools, and colors are also influencing new waves of masters.[4] [five]

Early periods [edit]

The earliest paintings were not representational only ornamental; they consisted of patterns or designs rather than pictures. Early pottery was painted with spirals, zigzags, dots, or animals. Information technology was only during the Eastern Zhou (770–256 BC) that artists began to stand for the earth effectually them. In imperial times (beginning with the Eastern Jin dynasty), painting and calligraphy in Prc were amidst the most highly appreciated arts in the courtroom and they were ofttimes practiced by amateurs—aristocrats and scholar-officials—who had the leisure time necessary to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy and painting were thought to be the purest forms of fine art. The implements were the castor pen made of animal hair, and black inks made from pine soot and animate being glue. In aboriginal times, writing, besides as painting, was done on silk. Even so, after the invention of paper in the 1st century AD, silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been profoundly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are.

Artists from the Han (206 BC – 220 AD) to the Tang (618–906) dynasties mainly painted the human figure. Much of what we know of early Chinese figure painting comes from burial sites, where paintings were preserved on silk banners, lacquered objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the expressionless or help their souls to get to paradise. Others illustrated the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius or showed scenes of daily life.

During the Vi Dynasties period (220–589), people began to capeesh painting for its own beauty and to write well-nigh fine art. From this time nosotros begin to learn about private artists, such as Gu Kaizhi. Fifty-fifty when these artists illustrated Confucian moral themes – such as the proper behavior of a wife to her married man or of children to their parents – they tried to brand the figures graceful.

Six principles [edit]

The "Six principles of Chinese painting" were established past Xie He, a writer, fine art historian and critic in 5th century China, in "6 points to consider when judging a painting" (繪畫六法, Pinyin: Huìhuà Liùfǎ), taken from the preface to his book "The Record of the Classification of Old Painters" (古畫品錄; Pinyin: Gǔhuà Pǐnlù). Go along in mind that this was written circa 550 CE and refers to "old" and "ancient" practices. The six elements that ascertain a painting are:

- "Spirit Resonance", or vitality, which refers to the period of energy that encompasses theme, work, and artist. Xie He said that without Spirit Resonance, there was no demand to expect further.

- "Bone Method", or the way of using the brush, refers not simply to texture and castor stroke, but to the close link between handwriting and personality. In his day, the fine art of calligraphy was inseparable from painting.

- "Correspondence to the Object", or the depicting of grade, which would include shape and line.

- "Suitability to Type", or the application of color, including layers, value, and tone.

- "Division and Planning", or placing and arrangement, corresponding to composition, infinite, and depth.

- "Manual by Copying", or the copying of models, not from life merely but too from the works of antiquity.

Sui, Tang and Five dynasties (581–979) [edit]

During the Tang dynasty, figure painting flourished at the regal court. Artists such as Zhou Fang depicted the splendor of courtroom life in paintings of emperors, palace ladies, and imperial horses. Figure painting reached the height of elegant realism in the art of the court of Southern Tang (937–975).

Most of the Tang artists outlined figures with fine blackness lines and used vivid color and elaborate detail. However, one Tang artist, the master Wu Daozi, used only black ink and freely painted brushstrokes to create ink paintings that were so exciting that crowds gathered to sentry him work. From his time on, ink paintings were no longer thought to be preliminary sketches or outlines to be filled in with color. Instead, they were valued every bit finished works of art.

Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, many paintings were landscapes, often shanshui (山水, "mountain water") paintings. In these landscapes, monochromatic and sparse (a style that is collectively called shuimohua), the purpose was not to reproduce the appearance of nature exactly (realism) only rather to grasp an emotion or temper, as if catching the "rhythm" of nature.

Song, Liao, Jin and Yuan dynasties (907–1368) [edit]

Painting during the Song dynasty (960–1279) reached a further development of landscape painting; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the apply of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. The shan shui style painting—"shan" pregnant mount, and "shui" meaning river—became prominent in Chinese mural art. The emphasis laid upon mural was grounded in Chinese philosophy; Taoism stressed that humans were but tiny specks in the vast and greater cosmos, while Neo-Confucianist writers frequently pursued the discovery of patterns and principles that they believed caused all social and natural phenomena.[vi] The painting of portraits and closely viewed objects similar birds on branches were held in loftier esteem, but landscape painting was paramount.[7] By the beginning of the Song Dynasty a distinctive landscape style had emerged.[8] Artists mastered the formula of intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the groundwork retained qualities of vast and infinite infinite. Afar mountain peaks ascension out of high clouds and mist, while streaming rivers run from afar into the foreground.[9]

There was a significant deviation in painting trends between the Northern Vocal period (960–1127) and Southern Song period (1127–1279). The paintings of Northern Song officials were influenced by their political ethics of bringing order to the earth and tackling the largest problems affecting the whole of lodge; their paintings often depicted huge, sweeping landscapes.[10] On the other hand, Southern Song officials were more than interested in reforming society from the bottom upwardly and on a much smaller scale, a method they believed had a better take chances for eventual success; their paintings oftentimes focused on smaller, visually closer, and more intimate scenes, while the background was often depicted as insufficient of particular as a realm without concern for the creative person or viewer.[10] This change in attitude from one era to the adjacent stemmed largely from the rising influence of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Adherents to Neo-Confucianism focused on reforming society from the bottom up, not the top down, which can exist seen in their efforts to promote small private academies during the Southern Song instead of the large state-controlled academies seen in the Northern Song era.[eleven]

Ever since the Southern and Northern dynasties (420–589), painting had become an art of loftier sophistication that was associated with the gentry grade as one of their main artistic pastimes, the others being calligraphy and poetry.[12] During the Song Dynasty there were avid art collectors that would frequently meet in groups to discuss their own paintings, equally well as rate those of their colleagues and friends. The poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) and his cohort Mi Fu (1051–1107) often partook in these diplomacy, borrowing art pieces to written report and copy, or if they really admired a piece so an exchange was frequently proposed.[13] They created a new kind of fine art based upon the three perfections in which they used their skills in calligraphy (the art of beautiful writing) to make ink paintings. From their time onward, many painters strove to freely express their feelings and to capture the inner spirit of their subject instead of describing its outward advent. The small round paintings popular in the Southern Song were oft collected into albums equally poets would write poems along the side to match the theme and mood of the painting.[10]

The "4 Generals of Zhongxing" painted by Liu Songnian during the Southern Vocal dynasty. Yue Fei is the second person from the left. It is believed to be the "truest portrait of Yue in all extant materials".[xiv]

Although they were gorging art collectors, some Song scholars did not readily appreciate artworks deputed by those painters found at shops or common marketplaces, and some of the scholars even criticized artists from renowned schools and academies. Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, points out that Song scholars' appreciation of art created by their peers was not extended to those who made a living simply every bit professional person artists:[15]

During the Northern Song (960–1126 CE), a new class of scholar-artists emerged who did non possess the tromp l'œil skills of the academy painters nor even the proficiency of common market place painters. The literati'southward painting was simpler and at times quite unschooled, still they would criticize these other 2 groups as mere professionals, since they relied on paid commissions for their livelihood and did not paint just for enjoyment or self-expression. The scholar-artists considered that painters who concentrated on realistic depictions, who employed a colorful palette, or, worst of all, who accepted monetary payment for their piece of work were no better than butchers or tinkers in the market. They were not to be considered real artists.[15]

However, during the Song catamenia, in that location were many acclaimed court painters and they were highly esteemed by emperors and the majestic family. One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage past the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original Along the River During the Qingming Festival ringlet, one of the most well-known masterpieces of Chinese visual art. Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127–1162) once commissioned an art projection of numerous paintings for the Xviii Songs of a Nomad Flute, based on the adult female poet Cai Wenji (177–250 Advert) of the earlier Han dynasty. Yi Yuanji achieved a high degree of realism painting animals, in particular monkeys and gibbons.[xvi] During the Southern Song period (1127–1279), court painters such as Ma Yuan and Xia Gui used strong black brushstrokes to sketch trees and rocks and pale washes to suggest misty space.

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), painters joined the arts of painting, poetry, and calligraphy by inscribing poems on their paintings. These three arts worked together to express the creative person's feelings more completely than i fine art could do alone. Yuan emperor Tugh Temur (r. 1328, 1329–1332) was addicted of Chinese painting and became a creditable painter himself.

The Chinese are of all peoples the nearly adept in crafts and attain the greatest perfection in them. This is well known and people have described information technology and spoken at length nearly it. No one, whether Greek or any other, rivals them in mastery of painting. They take prodigious facility in it. Ane of the remarkable things I saw in this connectedness is that if I visited one of their cities, and then came dorsum to it, I ever saw portraits of me and my companions painted on the walls and on paper in the bazaars. I went to the Sultan's metropolis, passed through the painters' bazaar, and went to the Sultan's palace with my companions. We were dressed as Iraqis. When I returned from the palace in the evening I passed through the said bazaar. I saw my and my companions' portraits painted on newspaper and hung on the walls. Nosotros each one of united states looked at the portrait of his companion; the resemblance was right in all respects. I was told the Sultan had ordered them to practise this, and that they had come to the palace while nosotros were there and had begun observing and painting us without our being enlightened of it. Information technology is their custom to pigment everyone who comes among them.[17]

Late imperial China (1368–1895) [edit]

The panorama painting "Deviation Herald", painted during the reign of the Xuande Emperor (1425–1435 AD), shows the emperor traveling on horseback with a large escort through the countryside from Beijing's Imperial Urban center to the Ming Dynasty tombs. Offset with Yongle, xiii Ming emperors were buried in the Ming Tombs of present-24-hour interval Changping Commune.

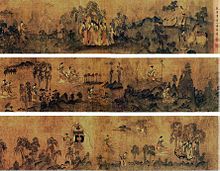

Outset in the 13th century, the tradition of painting simple subjects—a branch with fruit, a few flowers, or one or two horses—developed. Narrative painting, with a wider colour range and a much busier composition than Song paintings, was immensely pop during the Ming flow (1368–1644).

The first books illustrated with colored woodcuts appeared effectually this time; as colour-printing techniques were perfected, illustrated manuals on the art of painting began to exist published. Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students e'er since.

Some painters of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) connected the traditions of the Yuan scholar-painters. This grouping of painters, known as the Wu Schoolhouse, was led by the artist Shen Zhou. Another group of painters, known as the Zhe School, revived and transformed the styles of the Song court.

Shen Zhou of the Wu School depicted the scene when the painter was making his farewell to Wu Kuan, a good friend of his, at Jingkou.

During the early Qing dynasty (1644–1911), painters known as Individualists rebelled against many of the traditional rules of painting and constitute ways to limited themselves more directly through free brushwork. In the 18th and 19th centuries, nifty commercial cities such as Yangzhou and Shanghai became art centers where wealthy merchant-patrons encouraged artists to produce bold new works. Yet, similar to the phenomenon of central lineages producing, many well-known artists came from established creative families. Such families were concentrated in the Jiangnan region and produced painters such as Ma Quan, Jiang Tingxi, and Yun Zhu.[18]

A View of Henan Island (Honam), Canton, Qing dynasty

It was also during this period when Chinese trade painters emerged. Taking advantage of British and other European traders in popular port cities such as Canton, these artists created works in the Western fashion particularly for Western traders. Known as Chinese consign paintings, the trade thrived throughout the Qing Dynasty.

In the tardily 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese painters were increasingly exposed to Western fine art. Some artists who studied in Europe rejected Chinese painting; others tried to combine the all-time of both traditions. Among the almost beloved modernistic painters was Qi Baishi, who began life every bit a poor peasant and became a great master. His best-known works depict flowers and small animals.

Shop of Tingqua, the painter

Modern painting [edit]

"Portrait of Madame Liu" (1942) Li Tiefu

Beginning with the New Culture Movement, Chinese artists started to prefer using Western techniques. Prominent Chinese artists who studied Western painting include Li Tiefu, Yan Wenliang, Xu Beihong, Lin Fengmian, Fang Ganmin and Liu Haisu.

In the early on years of the Communist china, artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism. Some Soviet Union socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. This regimen was considerably relaxed in 1953, and later the Hundred Flowers Entrada of 1956–57, traditional Chinese painting experienced a significant revival. Along with these developments in professional fine art circles, there was a proliferation of peasant fine art depicting everyday life in the rural areas on wall murals and in open-air painting exhibitions.

During the Cultural Revolution, art schools were closed, and publication of art journals and major art exhibitions ceased. Major destruction was also carried out every bit function of the elimination of Four Olds entrada.

Since 1978 [edit]

Post-obit the Cultural Revolution, art schools and professional organizations were reinstated. Exchanges were set upward with groups of foreign artists, and Chinese artists began to experiment with new subjects and techniques. One particular case of freehand fashion (xieyi hua) may be noted in the work of the child prodigy Wang Yani (built-in 1975) who started painting at age iii and has since considerably contributed to the do of the style in contemporary artwork.

After Chinese economic reform, more and more than artists boldly conducted innovations in Chinese Painting. The innovations include: development of new brushing skill such every bit vertical direction splash h2o and ink, with representative artist Tiancheng Xie,[ citation needed ] creation of new way by integration traditional Chinese and Western painting techniques such as Sky Manner Painting, with representative artist Shaoqiang Chen,[xix] and new styles that express gimmicky theme and typical nature scene of certain regions such as Lijiang Painting Way, with representative artist Gesheng Huang.[ citation needed ] A 2008 fix of paintings by Cai Jin, most well known for her use of psychedelic colors, showed influences of both Western and traditional Chinese sources, though the paintings were organic abstractions.[xx]

Contemporary Chinese Art [edit]

Chinese painting continues to play an essential role in Chinese cultural expression. Starting mid-twentieth century, artists brainstorm to combine traditional Chinese painting techniques with Western art styles, leading to the style of new contemporary Chinese art. One of the representative artists is Wei Dong who drew inspirations from eastern and western sources to express national pride and get in at personal appearing.[21]

Iconography in Chinese painting [edit]

Water Manufacturing plant [edit]

As the landscape painting rose and became the dominant manner in North Song dynasty, artists began to shift their attention from jiehua painting, which indicates paintings of Chinese architectural objects such as buildings, boats, wheels and vehicles, towards landscape paintings. Intertwining with the regal landscape painting, water mill, an element of jiehua painting, though, is nonetheless used as an imperial symbol. Water mill depicted in the Water Mill is a representation for the revolution of technology, economic system, science, mechanical engineering and transportation in Song dynasty. It represents the government straight participate in the milling manufacture which tin influence commercial activities. Another show that shows the government interfered with the commercial is a wineshop that appears beside the water mill. The h2o manufacturing plant in Shanghai Scroll reflects the development in engineering and growing knowledge in hydrology. Furthermore, a h2o mill can besides be used to identify a painting and used every bit a literature metaphor. Lately, the water mill transform into a symbolic form representing the imperial court.

A Chiliad Miles of Rivers and Mountains by Wang Ximeng, celebrates the imperial patronage and builds upwards a bridge that ties the later emperors, Huizong, Shenzong with their ancestors, Taizu and Taizong. The water mill in this painting, unlike that is painted in previous Shanghai ringlet to be solid and weighted, it is painted to exist ambiguous and vague to friction match up with the court sense of taste of that time. The painting reflects a slow pace and peaceful idyllic style of living. Located deeply in a village, the water manufacturing plant is driven past the force of a huge, vertical waterwheel which is powered by a sluice gate. The creative person seems to be ignorance towards hydraulic engineering since he simply roughly drew out the machinery of the whole process. A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountainspainted by Wang Ximeng, a court artist taught directly past Huizong himself. Thus, the artwork A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountainsshould directly review the gustatory modality of the regal gustatory modality of the landscape painting. Combining richness vivid blue and turquoise pigments heritage from Tang dynasty with the vastness and solemn infinite and mountains from Northern Song, the scroll is a perfect representation of imperial power and aesthetic taste of the aristocrats.[22]

Image equally Word: Rebus [edit]

There is a long tradition of having hidden meaning behind certain objects in Chinese paintings. A fan painting by an unknown artist from North Vocal period depicts 3 gibbons capturing baby egrets and scaring the parents away. The rebus behind this scene is interpreted as celebrating the test success. Since another painting which has similar subjects—gibbons and egrets, is given the championship of San yuan de lu三猿得鹭, or Three gibbons catching egrets. Equally the rebus, the audio of the title can also be written equally 三元得路, pregnant "a triple offset gains [ane] power." 元represents "first" replaces its homophonous 猿, and 路means road, replaces 鹭. Sanyuan is firstly recorded as a term referring to people getting triple first place in an exam in Qingsuo gaoyi past a North Song writer Liu Fu, and the usage of this new term gradually spread across the country where the scenery of gibbons and egrets is widely accustomed. Lately, other scenery derived from the original paintings, including deer in the scene because in Chinese, deer, lu is as well a homophonous of egrets. Moreover, the number of gibbons depicted in the painting tin can exist flexible, not only limited to three, sanyuan. Since the positions in Song courts are held by elites who accomplished jinshi degree, the paintings with gibbons, egrets or deer are used for praising those elites in general.

Emperor Huizong personally painted a painting called Birds in a bloom wax-plum tree, features with two "hoary headed birds," "Baitou weng" resting on a tree branch together. "Baitou" in Chinese culture is allusion to true-blue honey and marriage. In a well-known dear poem, information technology wrote: "I wish for a lover in whose eye I alone exist, unseparated even our heads plough hoary." During Huizong's rule, literati rebus is embedded in court painting academy and became part of the test routine to enter the royal court. During Vocal dynasty, the connection between painters and literati, paintings and poem is closer.[23]

The Donkey Rider [edit]

"The land is broken; mountains and rivers remain." The poem by Du Fu (712-770) reflects the major principle in Chinese culture: the dynasty might change, but the mural is eternal. This timelessness theme evolved from Six Dynasty catamenia and early Northern Song. A donkey rider travelling through the mountains, rivers and villages is studied as an important iconographical character in developing of landscape painting.

The donkey rider in the painting Travelers in a wintry forest by Li Cheng is causeless to be a portrait painting of Meng Haoran, "a tall and lanky man dressed in a scholar apparently robe, riding on a small horse followed by a young servant." Except Meng Haoran, other famous people for example, Ruan Ji, ane of the seven sages of the Bamboo Grove and Du Fu, a younger gimmicky of Meng are also depicted as donkey rider. Tang dynasty poets Jia Dao and Li He and early Song dynasty elites Pan Lang, Wang Anshi appears on the paintings equally donkey passenger. Due north Song poets Lin Bu and Su Shi are lately depicted as donkey rider. In this specific painting Travelers in a wintry woods, the potential candidates for the ass passenger are dismissed and the graphic symbol can only be Meng Haoran. Meng Haoran has made more than than two hundred poems in his life only none of them is related with donkey ride. Depicting him every bit a donkey passenger is a historical invention and Meng represents a general persona than an private character. Ruan Ji was depicted equally ass rider since he decided to escape the office life and went back to the wilderness. The ass he was riding is representing his poverty and eccentricity. Du Fu was portrayed as the passenger to accent his failure in office achievement and also his poor living condition. Meng Haoran, similar to those ii figures, disinterested in office career and acted every bit a pure scholar in the field of poem by writing real poems with real experience and real emotional attachment with the landscape. The donkey rider is said to travel through time and space. The audience are able to connect with the scholars and poets in the past past walking on the aforementioned road as those superior ancestors accept gone on. Besides the ass rider, at that place is always a bridge for the ass to beyond. The bridge is interpreted to have symbolic pregnant that represents the road which hermits depart from capital city and their official careers and go back to the natural earth.[24]

Realm of the Immortals [edit]

During Song dynasty, paintings with themes ranging from animals, flower, landscape and classical stories, are used as ornaments in majestic palace, authorities function and elites' residence for multiple purposes. The theme of the art in display is carefully picked to reflect non only a personal taste, but likewise his social status and political accomplishment. In emperor Zhezong's lecture hall, a painting depicting stories class Zhou dynasty was hanging on the wall to remind Zhezong how to exist a adept ruler of the empire. The painting also serves the purpose of expressing his conclusion to his courtroom officers that he is an aware emperor.

The primary walls of the government office, also called walls of the "Jade Hall," meaning the residence of the immortals in Taoism are decorated by decorative murals. Nigh educated and respected scholars were selected and given the title xueshi. They were divided into groups in helping the Instituted of Literature and were described every bit descending from the immortals. Xueshi are receiving high social status and doing carefree jobs. Lately, the xueshi yuan, the place where xueshi lives, became the permanent authorities establishment that helped the emperor to make imperial decrees.

During Tang dynasty reign of Emperor Xianzong (805-820), the west wall of the xueshi yuan was covered by murals depicting dragon-like mountain scene. In 820–822, immortal animals like Mount Ao, flying cranes, and xianqin, a kind of immortal birds were added to the murals. Those immortal symbols all indicate that the xueshi yuan every bit eternal existing government office.

During Song dynasty, the xueshi yuan was modified and moved with the dynasty to the new capital Hangzhou in 1127. The mural painted by Song artist Dong yu, closely followed the tradition of Tang dynasty in depicting the misty sea surrounding the immortal mountains. The scenery on the walls of the Jade Hall which total of mist clouds and mysterious land is closely related to Taoism tradition. When Yan Su, a painter followed the mode of Li Cheng, was invited to paint the screen behind the seat of the emperor, he included elaborated synthetic pavilions, mist clouds and mountain landscape painting in his work. The theme of his painting is suggesting the immortal realm which accord with the entire theme of the Jade Hall provides to its viewer the feeling of otherworldliness. Another painter, Guo Xi made another screen painting for emperor Shenzong, depicting mountains in bound in a harmonized atmosphere. The image also includes immortal elements Mountain Tianlao which is one of the realms of the immortals. In his painting, Early Bound, the strong branches of the copse reflects the life force of the living creatures and implying the emperor'south benevolent rule.[25]

Images of women [edit]

Female characters are almost excluded from traditional Chinese painting under the influence of Confucianism. Dong Zhongshu, an influential Confucian scholar in the Han dynasty, proposed the three-bond theory maxim that: "the ruler is Yang and the subject is Yin, father is Yang and son is Yin…The husband is Yang, and the wife is Yin," which places females in a subordinate position to that of males. Under the 3-bond theory, women are depicted as housewives who need to obey to their husbands and fathers in literature. Similarly, in the portrait paintings, female characters are also depicted as exemplary women to elevate the rule of males. A hand roll Exemplary Womenby Ku Kai Zhi, a six Dynasty artist, depicted adult female characters who may be a wife, a girl or a widow.

During the Tang dynasty, artists slowly began to capeesh the beauty of a woman'due south body (shinu). Artist Zhang Xuan produced painting named palace women listening to music that captured women's elegance and pretty faces. Yet, women were still being depicted as submissive and ideal within male system.

During the Song dynasty, every bit the honey verse form emerged, the images associated with those love stories were made as attractive as possible to meet the gustatory modality of the male viewers.[26]

Landscape Painting [edit]

A timeline of Chinese mural painting from early Tang to the nowadays 24-hour interval

A landscape painting by Guo Xi. This piece shows a scene of deep and serene mount valley covered with snow and several old trees struggling to survive on precipitous cliffs.

Paradigm Shift in Chinese Mural Representation [edit]

Northern Song landscape painting dissimilar from Southern Song painting because of its paradigm shift in representation. If Southern Song period mural painting is said to exist looking inward, Northern Vocal painting is reaching outward. During the Northern Song catamenia, the rulers' goal is to consolidate and extend the elites value across the society. Whereas Southern Song painters decided to focus on personal expression. Northern Song landscapes are regarded as "real landscape", since the court appreciated the representation relationship between art and the external globe, rather than the relationship betwixt fine art and the artists inner vocalism. The painting, A Thou Miles of Rivers and Mountains is horizontally displayed and there are four mountain ranges arranged from left to correct. Similar to another early Southern Vocal painter, Zhou Boju, both artists glorified their patrons past presenting the gigantic empire images in blue and light-green landscape painting. The merely difference is that in Zhou's painting, there are five mountain ranges that arranges from right to left. The scenes in the Sothern Vocal paintings are about north mural that echos the memory of their lost north territory. All the same, ironically, some scholars suggested that Wang Ximeng's A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains depicts the scenes of the south not the n.[27]

Buddhist and Taoist influences on Chinese Landscape painting [edit]

The Chinese landscape painting are believed to be affected by the intertwining Chinese traditional religious behavior, for example, "the Taoist love of nature", and "Buddhist principle of emptiness," and can correspond the diversification of artists attitudes and thoughts from previous period. The Taoist dear of nature is not always present in Chinese landscape painting but gradually adult from 6 Dynasties period when Taoists Lao-tzu, Chuang-tzu, the Pao-p'u tzu's thoughts are reflected in literature documents. Apart from the contemporary Confucian tradition of insisting on homo cultivation and learning to be more than educated and build up social framework, Taoist persist on going back to homo'south origin, which is to exist ignorant. Taoists believe that if one discard wise, the robbery will terminate. If people abandon expensive jewelry, thieves will not exist. From Han Dynasty, the practice of Taoism was associated with alchemical and medicine fabricated. In society to meliorate pursuit Taoism conventionalities, Taoist need to continue pilgrim into specific mountains to connect themselves with the spirits and immortals that lived in those mountains. In the tertiary and fourth century, the practice of escaping society and going back to nature mediating in the countryside is further enhanced by a group called Vii Sages of the Bamboo Grove who would similar to escape from the civil unrest. The wise men fleet the earth and wonder in the countryside and enjoy the tranquil mural and forgot to return. The Taoism credo of forgetfulness, self-cultivation, harmonizing with nature globe, and purifying soul by inbound the isolated mountains to mediate and seek medicine herbs create the scene of landscape painting.

During Han Dynasty, the mountains appeared in the design of the artworks shows the prevalence part of mountain in Han society. The emperor would climb on to the mount to sacrifice and religion practice because mountains are idea to have connection between earth and heaven and can link man with spirits and immortals. And sometimes, mountains are depicted as mystical mountains" (shenshan), where sages and legendary animals settled. Hence, landscape painting is used as an object for Taoism practice which provide visualize form for religious ritual. During Six Dynasty period, the mural painting experienced a stylistic change which myth and poem depiction were introduced into the painting. For example, in Ku Kai-chih's "Nymph of the river" ringlet and "The Admonitions of the Courtroom Preceptress", audience are able to read narrative clarification and text accompanied past visualized images.

Furthermore, in Buddhism practice, the mountain also has an important office in religious practice. From iconographical point of view, a Buddha's image is essence in helping a believer to practise meditation. For case, Buddha's reflection epitome, or shadow, is assimilated the image of a mountain, Lushan. This assimilation is also recorded in a poem by poet from Six Dynasty menses who pointed out that the beauty and nominosity of the mountain tin can elevate the spiritual connection between homo and the spirits. Thus, the mural painting come into display Buddha's image in people's everyday ritual practice. Hui-yuan described in his poem that "Lushan seems to mirror the divine appearance" which unifies the two images—the true epitome and the reflection of Buddha. Moreover, spiritual acme tin be achieved by contemplating in forepart of landscape painting which describe the aforementioned mountain and path those old sages have been to. The painting contains both the spiritual force (ling) and the truth (li) of Buddha and besides the objects that no longer physically presence. Hui-Yuan's famous image is closely relation with its landscape scene indicating the trend of transformation from Buddha image to mural painting as a religious do.[28]

Early landscape painting [edit]

In Chinese society, there is a long-time appreciation of natural beauty. The early themes of poems, artworks are associated with agriculture and everyday life assembly with fields, animals. On the other hand, later Chinese painting pursuits majesty and grand. Thus, mount scenery become the near popular subject to paint because it'due south high which represent human eminence. Besides, mountain is stable and permanent suggests the eminent of the royal power. Furthermore, mountain is hard to climb showing the difficulties human will face up through their lives.

Landscape painting evolved under the influence of Taoist who fled from civil turbulence and prosecution of the authorities and went dorsum to the wilderness. However, the development of Taoism was hindered past Han dynasty. During Han dynasty, the empire expanded and enlarged its political and economic influence. Hence, the Taoism'southward anti-social belief was disfavored by the imperial government. Han rulers only favored portrait painting which enabled their image to be perpetuate and their civilians to see and to memorize their great leaders or generals. Landscape at that time simply focus on the copse for literary or talismanic value. The usage of mural painting as ornament is suspects to be borrowed from other societies outside Han empire during its expansion to the Near East. Landscape and animal scene began to appear on the jars, but the ornamentation has footling to practice with connection with the natural world. Also, there is evidence showing that the emerging of landscape painting is not derived from map-making.

During the 3 Kingdoms and Six Dynasty, landscape painting began to have connectedness with literati and the production of poems. Taoism influence on people's appreciation of landscaping deceased and nature worshipping superseded. However, Taoist still used landscape painting in their meditation just every bit Confucius uses portrait painting in their ritual do. (Ku Kai Chih's admonitions) During this time flow, the landscape painting is more coherence with variation trees, rocks and branches. Moreover, the painting is more elaborated and organized. The evolution in landscape painting during Vi Dynasty is that artists harmonized sprit with the nature. (Wu Tao-tzu) Buddhism might also contribute in affecting changes in mural painting. The artists began to show space and depth in their works where they showed mountain mass, distanced hills and clouds. The emptiness of the infinite is helping the believers meditating to enter the space of emptiness and pettiness.

The well-nigh important development in landscape painting is that people came to recognize the infinity variation of the nature world, and then they tended to make each tree individualized. Every landscape painting is restricted by storytelling and is dependent on artists retentivity.[29]

Dyads [edit]

Chinese landscape painting, "shanshui hua" ways the painting of mountains and rivers which are the ii major components that represents the essence of the nature. Shanshui in Chinese tradition is given rich meaning, for example mount represents Yang and river indicates Yin. According to Yin Yang theory, Yin embodies Yang and Yang involved in Yin, thus, mountain and river is inseparable and is treated as a whole in a painting. In the Mountains and rivers without stop, for case, "the dyad of the mountain uplift, subduction, and erosion and the planetary water wheel" is consistent with the dyad of Buddhism iconography, both representing austerity and generous loving spirit.[30]

Art as cartography [edit]

"Arts in maps, arts as maps, maps in arts, and maps every bit arts," are the four relationships between art and map. Making a distinction between map and art is difficult because there are cartographic elements in both paintings. Early on Chinese map making considered earth surface equally apartment, and then artists would non take projection into consideration. Moreover, map makers did not have the thought of map scale. Chinese people from Song dynasty called paintings, maps and other pictorial images as tu, so it's impossible to distinguish the types of each painting by name. Artists who paint mural as an artwork focus mainly on the natural beauty rather on the accurateness and realistic representation of the object. Map on the other hand should exist depicted in a precise style which more focus on the altitude and important geographic features.

The two examples in this example:

The Changjiang Wan Li Tu, although the date and the authorship are non clear, the painting is believed to be made in Song dynasty by examining the place names recorded on the painting. But based on the name of this painting, it is hard to distinguish whether this painting is painted every bit a landscape painting or equally a map.

The Shu Chuan Shenggai was once thought as the product done by North Song artist Li Gonglin, however, later bear witness disapproved this thought and proposed the engagement should exist changed to the cease of South Song and artist remains unknown.

Both those paintings, aiming to heighten viewers appreciation on the beauty and majesty of mural painting, focusing on the light condition and conveying certain attitude, are characterized as masterpiece of art rather than map.[31]

Meet also [edit]

- Chinese fine art

- Chinese Piling paintings

- Danqing

- Bird-and-bloom painting

- Gongbi

- Wǔ Xíng painting

- Three perfections – integration of calligraphy, poesy and painting

- List of Chinese painters

- List of Chinese women artists

- The Four Great Academy Presidents

- 8 Eccentrics of Yangzhou

- Lin Tinggui

- Qiu Ying

- Mu Qi

- History of painting

- History of Asian art

- Eastern fine art history

- Japanese painting

- Korean painting

- Cantonese school of painting

- Eight Views of Xiaoxiang

Notes [edit]

- ^ Sickman, 222

- ^ Rawson, 114–119; Sickman, Chapter xv

- ^ Rawson, 112

- ^ a b (Stanley-Bakery 2010a)

- ^ (Stanley-Baker 2010b)

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 162.

- ^ Morton, 104.

- ^ Barnhart, "Three One thousand Years of Chinese Painting", 93.

- ^ Morton, 105.

- ^ a b c Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 163.

- ^ Walton, 199.

- ^ Ebrey, 81–83.

- ^ Ebrey, 163.

- ^ Shao Xiaoyi. "Yue Fei's facelift sparks debate". Red china Daily. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ^ a b Barbieri-Low (2007), 39–forty.

- ^ Robert van Gulik, "Gibbon in Communist china. An essay in Chinese Animal Lore". The Hague, 1967.

- ^ Gibb 2010, p. 892.

- ^ Lan Qiuyang 兰秋阳; Xing Haiping 邢海萍 (2009), "清代绘画世家及其家学考略" [The aloof fine art families of the Qing and their learning], Heibei Beifang Xueyuan Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) (in Chinese), 25 (3): 24–26

- ^ "【社团风采】——"天堂画派"艺术家作品选刊("书法报·书画天地",2015年第2期第26–27版)". qq.com . Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ Goodman, Jonathan (August 13, 2013). "Cai Jin: Return to the Source". Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ "Modernistic & Gimmicky Chinese Art". Williams Higher Museum of Art.

- ^ Liu, Heping (December 2002). ""The Water Mill" and Northern Song Majestic Patronage of Art, Commerce, and Scientific discipline". The Art Bulletin. 84 (iv): 566–595. doi:ten.2307/3177285. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3177285.

- ^ Bai, Qianshen (January 1999). "Image equally Word: A Study of Rebus Play in Vocal Painting (960-1279)". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 34: 57–12. doi:x.2307/1513046. ISSN 0077-8958. JSTOR 1513046. S2CID 194029919.

- ^ Sturman, Peter C. (1995). "The Donkey Rider equally Icon: Li Cheng and Early on Chinese Landscape Painting". Artibus Asiae. 55 (1/2): 43–97. doi:10.2307/3249762. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249762.

- ^ Jang, Scarlett (1992). "Realm of the Immortals: Paintings Decorating the Jade Hall of the Northern Vocal". Ars Orientalis. 22: 81–96. JSTOR 4629426.

- ^ Fong, Mary H. (1996). "Images of Women in Traditional Chinese Painting". Woman's Art Journal. 17 (ane): 22–27. doi:ten.2307/1358525. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 1358525.

- ^ Duan, Lian (January ii, 2017). "Paradigm Shift in Chinese Mural Representation". Comparative Literature: East & W. 1 (1): 96–113. doi:10.1080/25723618.2017.1339507. ISSN 2572-3618.

- ^ Shaw, Miranda (April 1988). "Buddhist and Taoist Influences on Chinese Mural Painting". Journal of the History of Ideas. 49 (ii): 183–206. doi:10.2307/2709496. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709496.

- ^ Soper, Alexander C. (June 1941). "Early Chinese Landscape Painting". The Fine art Bulletin. 23 (two): 141–164. doi:10.2307/3046752. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3046752.

- ^ Hunt, Anthony (1999). "Singing The Dyads: The Chinese Landscape Scroll and Gary Snyder's Mountains and Rivers Without End". Journal of Modern Literature. 23 (1): 7–34. doi:10.1353/jml.1999.0049. ISSN 1529-1464. S2CID 161806483.

- ^ Hu, Bangbo (June 2000). "Fine art as Maps: Influence of Cartography on Two Chinese Landscape Paintings of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE)". Cartographica: The International Periodical for Geographic Information and Geovisualization. 37 (two): 43–56. doi:10.3138/07l4-2754-514j-7r38. ISSN 0317-7173.

References [edit]

- Gibb, H.A.R. (2010), The Travels of Ibn Battuta, Ad 1325-1354, Volume Four

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Volume of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Printing, ISBN 9780714124469

- Stanley-Bakery, Joan (May 2010a), Ink Painting Today (PDF), vol. 10, Centered on Taipei, pp. 8–11, archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2011

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman L & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of China", Pelican History of Fine art, third ed 1971, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC seventy-125675

- Stanley-Bakery, Joan (June 2010b), Ink Painting Today (PDF), vol. 10, Centered on Taipei, pp. xviii–21, archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012

Further reading [edit]

- Barnhart, Richard, et al., ed. Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

- Cahill, James. Chinese Painting. Geneva: Albert Skira, 1960.

- Fong, Wen (1973). Sung and Yuan paintings . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0870990847. Fully online from the MMA

- Liu, Shi-yee (2007). Straddling East and West: Lin Yutang, a modern literatus: the Lin Yutang family collection of Chinese painting and calligraphy. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9781588392701.

External links [edit]

- Chinese Painting at China Online Museum

- Famous Chinese painters and their galleries

- Chinese painting Technique and styles

- Cuiqixuan – Within painting snuff bottles

- Between 2 cultures : belatedly-nineteenth- and twentieth-century Chinese paintings from the Robert H. Ellsworth drove in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Fully online from the MMA

- A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting: a series of more than than 20 video lectures past James Cahill.

- Gazing Into The By – Scenes From After Chinese & Japanese Painting: a series of video lecture by James Cahill.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_painting

0 Response to "Pang Yande Chinese Folk Art Painting on Leaves Buy Online"

Post a Comment